Masan was a small agricultural and fishing village when it opened to foreign trade on May 1st, 1899. Though its neighbor, Jinhae, would later become an important Japanese naval base, modern Masan had a twelve year head start on its sister city. Development rights in Masan were eagerly sought by both the Japanese and Russian governments at the turn of the twentieth century due to the harbor’s strategic position, natural deep water, and absence of ice during winter. It is often thought that Imperial Japan had virtual free reign in many Korean ports after the 1876 treaty, but it wasn’t until after 1898 that this became more true.1 Even after 1898, the island nation had trouble controlling Masan and keeping Russia out of the area.

The Russian Connection

Russian interest in Masan can specifically be seen as early as 1897 when the imperial nation “demanded” permission to build a coaling station in the area.2 Bear in mind that this is prior to the port’s official opening, yet it isn’t the only instance of Russia asking for rights in non-treaty [unopened] ports.3 After arriving in Seoul in August of 1898, a Russian diplomat named A. I. Pavlov and “his consuls became active in the south at places like Masampo [Masan], Mokpo, and Kojedo [Geojedo],” again showing interest in establishing a naval foothold along the southern coast.4

At this time, while a Russian land lease was being discussed with the Korean government, a man named Hakuma Fusataro was buying up some of the land claimed under the Russian lease.5 Perhaps unbeknownst to Russia, the lots purchased by Hakuma and other non-military Japanese citizens6 were then transferred to the Japanese military. It is unclear whether or not this was planned from the beginning, but given that Japan would later offer a bribe to the Korean government asking them to tell Russia that Geojedo was already spoken for by Japan,7 its possible the land switch was made on purpose. After putting a lot of pressure on the Korean cabinet, Russia still couldn’t obtain the land lease in Masan. In a move that would weaken all Russian influence across Korea, the Tsarist country then threatened to withhold financial and military aid from Korea.8 Korea “gladly” accepted,9 maybe because it would rid them of the nagging that came with ties to the imperial nation. (Note that King Gojong had a close relationship with the Russian legation in Seoul around this time, which calls into question parts of the analysis here. However, it may also suggest a distinction between the relationship of Gojong with Russians in Korea and the relationship of Korea as a country with Russia in general.) Russia followed through with its threat, taking its military and financial advisers home and closing the Russo-Korea Bank.10 The Nishen-Rosen treaty, signed on April 25, 1898, then helped Japan in lessening Russian influence in Korea by declaring it an independent state.11 This outcome is interesting given King Gojong’s close relationship with the Russian consulate in Seoul, offering further evidence of how politically complicated the last few years of the 19th century were.

The next year, after Masan was opened in May of 1899, both Japan and Russia built consulates in Masan, Japan’s done in a Renaissance style and Russia’s in a “colonial” style.12 A second attempt to acquire a concession was made when “the Russian navy tried to obtain a piece of land for its own use”13. A Japanese colonel named Tamura Iyozo took steps to counter this Russian move. In the following month of June, he was noted for saying of the situation that, “if Russia gets her hands on Masampo, Japan must become useless”,14 showing how important Masan was to the Japanese.

Later, in February of 1900, a rumour spread regarding Pavlov attempting to obtain a land lease for a third time when a “large Russian squadron including the battleships Rossiya, Donskoi, and Rurik sailed from Port Arthur and weighed anchor at Masampo threateningly.”15 In a move that clearly showed their interest in keeping other imperial powers out of the Geojedo area, the Japanese proposed that a Russian concession on the southern coast should be contained within Masan’s harbor and not have any “command” over the water of Geojedo.16 This may also show that Japan thought Russia would inevitably gain a land lease in the area and this move could have been an attempt at controlling the situation. It was at this time that the issue regarding the Russian claimed land that had been bought by Japanese citizens and given to the Japanese military was solved through a simple trade. Then, in September of 1900, Russia finally got its concession at Pankumi, Masan.17 Through a secret pact made between Japan and Russia, both countries would stay out of Geojedo.18

If Russia had gained a strong foothold in Busan or Geojedo, it would have created a strong naval line circling the entire Korean peninsula from Port Arthur, to Masan, to Geojedo or Busan, and up to Vladivostok. The Japanese were surely aware of this as they went to great lengths to keep Russia from completing this circle and out of the Korean waters near Tsushima. It is also during 1900 that we can see two important documents. The first, perhaps made around the time of the granting of Russia’s concession at Masan, is a map of the port area with the Romanov seal on it.19 The second, which shows just how fast the Japanese were in trying to dominant Masan, is a 1900 reclamation plan drawn up for Masan’s port development.20 Note that this is in contrast to Jinhae, which saw a six year difference between the time of the city’s boundary drawing and the creation of its official urban blueprint. Masan’s port was opened in 1899, and it’s development plan draw up just one year later.

Tensions between the two imperial powers then cooled before escalating again in 1903, a year where a moderate amount of information about Masan was being printed by the New York Times. It discussed the Russian desire to develop Masan’s ice-free port after their expensive failure at Dalian (China), where an incredible 17,000,000 rubles21 were spent for the construction of a breakwater that caused the harbor water to freeze.22 The newspaper also mentioned Russian and Japanese naval movements, but never discussed the political implications of Russia possibly obtaining a circle of ports around Korea. (Had Russia gained port concessions in southern Korea, they would have had a powerful naval loop around the country.) It did, however, mention some of the confusion surrounding the various reports coming out at the time.23

In October of 1903, some ninety Russian warships from Port Arthur docked next to Japan’s fleet in Masan while diplomatic negotiations took place in Tokyo.24 Perhaps as part of a race to gain influence in the area, Japan was reported a few days later as having obtained a concession for the construction of a railway at Masan’s port.25 Though it is unclear what happened exactly, by November the New York Times reported that Japan had “thwarted the Russian attempt to secure” Masan.26 About four months later, war broke out between the two empires.

Urban Planning and Early Modern City Life

Masan’s port was developed according to the previously mentioned Japanese reclamation plan, where tons of earth were moved to create some 78,300 square meters (~19 acres) of new coastline.27 Though it was said that Masan was “almost devoid of mud flats”,28 a 1946 U.S. military map shows there were some wetlands in the area even after liberation.29 Most of the city was built south of present day Sanho Park (산호공원), a place that has since been engulfed by modern urban sprawl. When the original foreign settlement plan was first drawn up, it covered a smaller section of the coastline. The blueprint interestingly included the names of the foreign ministers to Korea from Japan, France, China, Russia, Germany, and the U.S.30

The southern end of the city was densely populated and contained the City Hall, Customs House, Joseon Steamship Company, Siksan Bank, a gendarme building (pictured further below), a health station, and the residences of the mayor, chief of police, and municipal employees by the end of the Japanese occupation.31 Just a bit further south in the hills were military structures and army residences that have since been replaced by newer, large apartment blocks and a hospital.32 Masan Station, which was established around 1905,33 sat in the middle of the coastline, but the city had at least three rail stations and two separate lines by 1946. Also in the area were some schools, the Changwon County Office, an isolation hospital, at least one church, railroad workers’ quarters, an electric company, the tax office, Masan Provincial Hospital, and the city’s courthouse.34

A slaughter house, which was the place for the lowest of all professions during Joseon and still may not have been very respected during modernization, was located near present day Muhak Elementary School (무학초등학교) in the mid 1940s as well. The northern section was home to both Gumasan Station and Bukmasan Station. At the end of the Japanese occupation, you could have seen the Shokusan Bank, a salt plant, some warehouses, a rice mill, Masan Prison, a credit association, some cotton and textile businesses, and at least two churches in the area.35

Like a number of colonial cities, it seems a spatial split was formed over time, where Japanese residents lived in one area and Koreans in another. This was even observed by a German geographer in 1945 who referred to “Old Masan” as being a “Korean farming village” and “New Masan” as being “constructed exclusively in Japanese style.”36 Here, the author is writing less of time and more of space by making note of the stark contrast between the different communities that simultaneously existed within early modern Masan. The writer called attention to the location of “New Masan” as being two kilometers along the bay away from “Old Masan”, indicating that Koreans generally lived away from the city center.37 At the time of his writing, Masan had a population of 32,411 people, with eighteen percent being Japanese.38 During Masan’s early years, the Japanese population was quite small, but 103 people were already recorded as being there in 1899.39 The male Japanese population curiously fluctuated between 1899 and 1903 while the female Japanese population slowly increased.40 The total Japanese population then steadily increased from 1904 on as the port developed into a typical colonial commercial center under Japanese influence.41

While much of Masan’s early modern cityscape was still intact in the 1970s, by the 1980s a lot had changed due to industrialization. Today, very, very little of Masan’s old architecture remains. On the one hand, it is impressive that the city has been able to reinvent itself so quickly. On the other, considering its historic importance as a colonial era rail-sea interchange, it’s a shame so much of its tangible history has been lost.

Gapo-dong

Beginning with the city’s most southerly area, this is the place that was previously mentioned as having some military structures and residences. In June of 1946, just a year after Korea’s liberation, Masan National Tuberculosis Sanitarium, a kind of nursing home, opened in Gapo-dong.42 The hospital area, which seemed to have been filled with 1970s-80s styled block buildings, was completely bulldozed in the summer of 2015 save for the small, lone Bethel Church. Sadly, this too was then destroyed in June. Built in 1964, it might be difficult to argue it being worthy of preservation, and it doesn’t even really fall within the scope of this blog, but there are a couple of reasons for why I include it here.

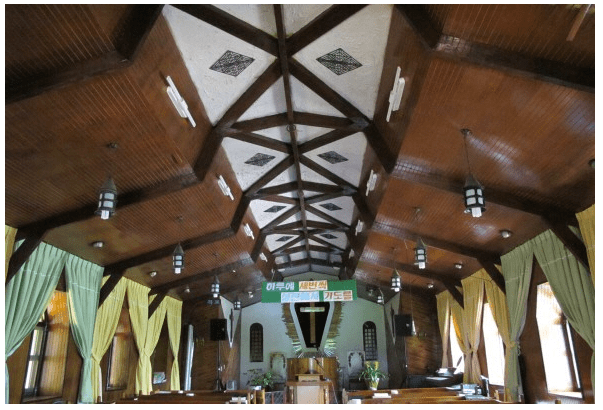

First, it is a prime example of the on-going, indiscriminate destruction of old architecture in Korea. That being said, it does seem that the church was the last building to get knocked down, maybe – just maybe – meaning that its destruction was being reconsidered. Second, Bethel Church stood as a flawless example of mid-century modern architecture. In fifty years’ time, someone might be looking for examples of mid-century modern buildings in Masan, and this would have been a great one to examine. It seems to have been built of concrete with a stone facade. Photos of the interior show wood being used throughout with a funky, almost Frank Lloyd Wright inspired, ceiling. The bell tower was saved but it is unclear whether or not it will stick around. I haven’t visited the site since it is in the middle of a construction zone outside of the city center, but it appears at least one guy got in to photograph it. However, I’ve marked the location of the bell tower on the map at the end of this blog post.

Wolnamdong 3(sam)-ga

The best preserved colonial structure in Masan is a former military police detachment or gendarme officially referred to as the Masan Branch of the Japanese Military Police. Built in 1926, its use of contrasting red and dark gray or black brick is similar to that of colonial Catholic cathedrals in Korea. The keystones above its arched, almost French styled, windows and door give the building a somewhat regal and authoritative aesthetic. At the time of its use it was only staffed by eight people.43 Curiously, a closed off section can be seen on its eastern wall. Though this is pure speculation on my part, it kind of looks like it may have been a drop off bay for police vehicles. Its placement seems too awkward to have been a window, and it’s too high off the ground to have been a normal door.

Janggundong 1(il)-ga

Up a bunch of steps, on the top of a hill reinforced by a stone retaining wall, sit three colonial houses. Surely the homes of some important or wealthy individuals, these houses could easily be the historical and architectural jewels of Masan if preservation groups ever got a hold of them. These homes sat in the middle of downtown right across the street from a grade school and one block away from the postal employees’ residence. The Changwon County Office and Masan Station were just three or four blocks to the southeast. Given their location, these houses may have served public officials, though without more information it is difficult to tell. In their current state they are practically unvisitable. Two of the buildings are walled-in, with at least one being presently occupied. The entire hill is covered in vegetation and debri, making it incredibly difficult to get any decent photographs.

The other house is on the left as one walks up the stone stairway. Its gorgeous front porch has red brick at the base of its supports while the windows and doors all appear to be original (possibly even the glass). Some parts of the roof have been covered in tin or plastic imitation tile – and it doesn’t look like the original is underneath it. The entire structure is not only blocked off by trees, but also by shipping pallets and discarded wood chunks that, hopefully, are indicative of some kind of potential restoration work.

Janggundong 3(sam)-ga

Northeast of the Janggun-dong Hill Houses is a small strip of buildings that made up an old brewery established in 1909. One of at least seven liquor manufacturers in Masan at the time, it seems they were all well known for their sake.44 The previously mentioned brewery sits next to the site of the old Chilseong Brewery, which later became the Samgang Brewery after liberation.45 The Chilseong/Samgang Brewery had several nice wooden Japanese buildings, and a larger one that was speculated as being the company president’s house.46 Unfortunately, nothing remains of it today. The city of Masan, in their infinite wisdom, allowed the destruction of this historical site just a few years ago despite local protest.47 It was replaced by a series of small, cookie-cutter, one-room styled apartment buildings. By clicking on this sentence, you can see an awesome article (in Korean) showing photos of the area before it was bulldozed and features a great sketch of the original structures. The photos below are of the remaining brewery structures.

Wanwol-dong

On the campus of Seong Ji Girls’ High School (성지여자고등학교) across from Janggun Stream (장군천), sit two important early modern buildings that are part of the legacy of the Catholic church in Masan. The first building pictured below is Saint Joseph Cathedral, a wooden and granite building constructed in a blend of Romanesque and Renaissance styles. Built in 1928, it is the oldest Catholic church in this province.

The second building is the school itself, which sits in front of Saint Joseph. Though it has been renovated and extended, the original stones, which seem to match the cathedral’s in both age and type, are still there. While I couldn’t get much information out of him, the security guard seemed to think they were both built around the same time. He was also a bit hesitant to let a male wander around a girls’ school and insisted on showing me around himself, limiting me from getting any distance shots of the school building. Regardless, he was nice enough and I appreciated him allowing me to take a look around.

The second building is the school itself, which sits in front of Saint Joseph. Though it has been renovated and extended, the original stones, which seem to match the cathedral’s in both age and type, are still there. While I couldn’t get much information out of him, the security guard seemed to think they were both built around the same time. He was also a bit hesitant to let a male wander around a girls’ school and insisted on showing me around himself, limiting me from getting any distance shots of the school building. Regardless, he was nice enough and I appreciated him allowing me to take a look around.

The church started while Russia and Japan were fighting for land in 1900. Like a number of churches in Korea, this one began in a small thatched-roof cottage. Founded by a French priest named Emille Taquet, another man named Fules Bermond is credited with the construction of the present 1928 structure. However, as we’ll see in another neighborhood below, it isn’t the only remaining Catholic building left in Masan. A few more old renovated buildings can be seen across the street from the high school along Janggun Stream.

The church started while Russia and Japan were fighting for land in 1900. Like a number of churches in Korea, this one began in a small thatched-roof cottage. Founded by a French priest named Emille Taquet, another man named Fules Bermond is credited with the construction of the present 1928 structure. However, as we’ll see in another neighborhood below, it isn’t the only remaining Catholic building left in Masan. A few more old renovated buildings can be seen across the street from the high school along Janggun Stream.

Burim-dong

In this neighborhood there are at least two more colonial era buildings, each on different streets. One has been painted in a picturesque light blue and might retain its original windows and roof tiles. A new sign on the facade indicates that it is, or just recently was, some kind of academy for studying philosophy for women. The other building pictured below has had its facade renovated and windows changed, yet its general frame still remains.

Namseong-dong and Seoseong-dong

These two neighborhoods, including present day Odong-dong, made up the immediate port area that was previously described as having the Shokusan Bank and a number of other industrial and financial businesses. The city has also put up a stone plaque in the area indicating that Masan’s first Korean-founded joint-stock exchange company, Wondong Trading Co. Ltd., was established in Namseong-dong in September of 1919. An intersection in Namseong-dong neighborhood retains no less than five colonial buildings, the most noteworthy of which is a handsome red brick structure that, given its design, may have served a company. Two of its walls are built at an angle, perhaps showing the direction of the original streets, which almost come to a point before squaring off at a section emphasized by a striking diamond window – a common window design found in colonial homes.

Another two story colonial building that has since had its exterior changed sits on Happo-ro. Based on the 1946 U.S. military map, it seems the present day streets southeast of Happo-ro, which includes this block of buildings, have changed since liberation, explaining why these structures appear to be crooked and ungrid-like. None of the structures on this block are protected by the government.

There are two more city blocks across from Happo-ro that are worth mentioning. The first one contains the seat of the Catholic diocese of Masan, Namseongdong Cathedral. Its facade has been completely redone, and the tower is new, but original stone and brick can still be seen. The main hall was constructed in July of 1951, making it noteworthy for being built during a time when money and resources were generally scarce due to the Korean War. It bears mentioning that the red bricks used in structures after the 1950s are a lot different from the ones used in colonial era buildings. This cathedral is then interesting for having still used a style of red brick that is more similar to colonial brick than post-war brick. Some of this brick can even be seen under the gate.

Behind the church is a row of a couple of minor wooden and brick colonial buildings. Interestingly, the wall of one building that has since been torn down still remains in order to form a boundary between properties. It has been sprayed over with cement on one side (last picture below), and an old window can just barely be seen down the alleyway (second picture below).

It also bears mentioning that old red brick walls can be found scattered throughout Masan, like the one pictured below in this same neighborhood. Used as boundaries like the previously mentioned wall, they offer a vague glimpse into what occupied the space before. One more tiny building can be found down the street, crammed up against a parking lot.

One block west from Namseongdong Cathedral, in what is technically Seoseong-dong, we can see a few more minor colonial buildings. Most of them aren’t anything special, and a few of them are hidden behind signs and facade add-ons (first picture below), but one Japanese house still retains its gorgeous decorative roof supports under the eaves of the gabled roof. Its old clay walls can be seen in some places, but it seems that most of its facade has changed. A wooden warehouse looking structure can be seen a few more steps up the street.

Sanho-dong

This neighborhood likely took its name from Sanho-ri, a small village at the foot of a small mountain (present day Sanho Park) that was later engulfed by Masan as the city grew after liberation. It seems a patch of wetlands stood between the previously mentioned neighborhoods and the mountain. The early modern buildings in this area can then be found at the foot of this mountain, between present day Sanho Park and Masan Yongma High School. The first one is a large structure with chimneys and ceramic roof tiles. Though I wasn’t able to get a great photo of the facade, a view from the front shows the tip of its gabled roof and impressive old gate that is reminiscent of the Jeong Pediatric Clinic in Daegu. A minor two-story colonial building can be seen nearby as well.

One of the most interesting finds in Masan is what appears to have been the former house of writer and literary theorist Ji Ha-ryeon.48 Born on July 11, 1912 in Geochang county, her real name was Lee Hyun Wook. Ji Ha-ryeon came from a wealthy family that allowed her to study in Tokyo, Japan. In 1936, she met a divorced man named Imhwa in Masan and they married. During the 1940s, a literary critic recommended she begin a career in writing, leading to the creation of at least eight works. Post-liberation, she joined the Joseon Literature Alliance with her husband, Imhwa, and moved to Manchuria. They remained there until after the Korean War, where Imhwa was killed for allegedly spying. Sadly, after failing to find her deceased husband’s body, it is said that Ji Ha-yreon lost her mind. She presumably died in North Korea shortly after. Ji Ha-ryeon’s story stands as a tragic representation of how Korea’s split was able to affect anyone regardless of status.49

The former writer’s Masan house is a colonial period building dating to the 1930s.50 Its facade has obviously changed, but parts of the original exterior wood paneling can be seen in a few places. Most curious of all is how the interior is scorched black from a recent fire. I didn’t fall through any ceilings, so it seems to be at least somewhat structurally sound, but judging by what does remain of its interior, it isn’t very true to the colonial era anymore. The main hall on the first floor where you enter shows that the room could have been divided with moving partitions. Also, note the built in wall shelves. It’s possible these were originally a tokonoma or some other display case that was later converted to shelving. Either way, recessed spaces of any kind were usually built by the wealthy.

In one seemingly untouched room on the first floor near the kitchen and a staircase, a clean calendar from July 2015 still remains hanging on the wall, offering further evidence that the fire was recent. In addition to the first floor room with the calendar, which is on the left side of the house relative to the entrance, the room in the right corner also seems untouched (second picture below).

While the damage is pretty bad throughout, some interesting features can still be seen. For example, there are two staircases on either side of the main room on the first floor. The left staircase (first picture below), by the kitchen and the room with a calendar, is a bit bigger than the one on the right (second picture below), which is narrow and twisting. On the second floor (third picture forward), we can also see the remains of a fireplace and what looks to have been a European styled diamond lattice window. The rafters have been severely burned and sections of the roof are missing. One second floor room also remains unburned. Its interior is mostly in post-industrialization Korean style, but the frosted glass could be original as the material was sometimes used in colonial era buildings.

The home is walled in with more of that colonial era red brick. An old wooden house sits next to it, which may be occupied (pictured below). When I visited the site, I spoke with a man who was tending a small vegetable garden and at least acted like he was in charge.51 Unfortunately, the house doesn’t seem to be protected by the government. The good news is that the structure sits out of the way on a mountainside, meaning it is less likely to get bulldozed than if it were located downtown.

Bongam-dong

North of this neighborhood, just a fifteen minute walk outside of the city, is the Bongam Reservoir, a water supply and dam built in 1930. Its stones were uniformly stacked and mortared, with the upper third section being built at an angle for structural support. This construction method was favored by the Japanese when building foundations for hillside structures and can be seen in old buildings throughout the Korean peninsula. Like a lot of civic projects in Korea, its construction made use of forced, or “conscripted,” labor, and came at a time when people were still using wells and streams. Again, it was generally the case that utilities would only be available to the downtown area of a colonial Korean city. This further created a socio-economic split between Japanese residents and Korean residents as it was mainly the Japanese and a handful of exceptionally wealthy Koreans who developed and resided in the urban areas.

To see the entire Flickr gallery, click here.

This is a rewrite of an older blog post about Masan that has since been deleted. I spent more time researching the city and came across more buildings that I wanted to make note of. Everything in the old post has been included here, it has just been expanded upon.

Footnotes

1Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

2Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

3“RUSSIA’S SUCCESS IN KOREA,” New York Times, Sept. 13, 1903.

4Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

5Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

6Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

7Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

8Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

9Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

10Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

11Bong-youn Choy, Korea: A History (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971).

12호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (32) – 개항이후,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

13Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

14Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

15Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

16Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

17Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

18Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Routledge, 2014), 61.

19호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (23) – 개항기,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

20호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (24) – 개항기,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

21Maybe about $229,729,729 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation.

22“RUSSIA’S EASTERN POLICY IS AN ADMITTED FAILURE,” New York Times, Nov. 13, 1903.

23“Article 6 – No Title,” New York Times, Oct. 20, 1903.

24“RUSSIAN FLEET AT KOREA?” New York Times, Oct. 9, 1903.

25“KOREAN CONCESSION FOR JAPAN,” New York Times, Oct. 12, 1903.

26“RUSSIA’S EASTERN POLICY IS AN ADMITTED FAILURE,” New York Times, Nov. 13, 1903.

27호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (24) – 개항기,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

28Hermann Lautensach, Korea: A Geography Based on the Author’s Travels and Literature (Braunschweig: Springer-Verlag, 1988), 340.

29Army Map Service, MASAN KYONGSANG-NAMDO (KEISHO-NANDO), KOREA [map]. 1:12,500. Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, 1946.

30호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (22) – 개항기,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

31Army Map Service, MASAN KYONGSANG-NAMDO (KEISHO-NANDO), KOREA [map]. 1:12,500. Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, 1946.

32Army Map Service, MASAN KYONGSANG-NAMDO (KEISHO-NANDO), KOREA [map]. 1:12,500. Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, 1946.

33호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (32) – 개항이후,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

34Army Map Service, MASAN KYONGSANG-NAMDO (KEISHO-NANDO), KOREA [map]. 1:12,500. Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, 1946.

35Army Map Service, MASAN KYONGSANG-NAMDO (KEISHO-NANDO), KOREA [map]. 1:12,500. Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, 1946.

36Hermann Lautensach, Korea: A Geography Based on the Author’s Travels and Literature (Braunschweig: Springer-Verlag, 1988), 340.

37Hermann Lautensach, Korea: A Geography Based on the Author’s Travels and Literature (Braunschweig: Springer-Verlag, 1988), 340.

38Hermann Lautensach, Korea: A Geography Based on the Author’s Travels and Literature (Braunschweig: Springer-Verlag, 1988), 340.

39호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (27) – 개항이후,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

40호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (27) – 개항이후,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

41호겅도, “그림으로 보는 마산도시변천사 (27) – 개항이후,” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

42김민지, “‘결핵환자 안식처’ 창원 벧엘교회 철거,” idomin, 2015.

43문화재청 (Cultural Heritage Administration), “마산헌병 분견대,” 문화재검색.

44허정도, “잊혀진 마산의 청주공장을 찾아서 (2),” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

45 허정도, “잊혀진 마산의 청주공장을 찾아서 (2),” 허정도와 함께 하는 도시이야기 (2010).

46Kim Chu-wan, “술의 도시에 남아있는 일제시대 술공장,” 김훤주 (2009).

47박동필, “물 좋은 마산 옛 삼광청주 공장을 살리자,” 국제신문 (2011).

48김민지, “마산야구장 바로 옆에서 불난 집 알고봤더니,” idomin (2015).

49“지하련,” 위키백과 (2015).

50김민지, “마산야구장 바로 옆에서 불난 집 알고봤더니,” idomin (2015).

51It really isn’t clear who owns this building, but it seems to be private. The guy I talked to could have just been squatting on the garden area, or he could have been a caretaker. Anyway, I asked for permission before taking photos here.

Building Locations

Pingback: Jinhae | Colonial Korea

Pingback: Gunsan | Colonial Korea

Pingback: Mokpo | Colonial Korea

Pingback: Suncheon | Colonial Korea

Pingback: The Comfort, Construction, and Social Views of Common Homes in Colonial Korea – Colonial Korea